Results are in: Companies are not realizing productivity gains they hoped for with AI

Turns out - AI is not an easy drop in the bucket. Here is why.

The AI hype is quieting down.

McKinsey reports that 72% or organizations are using AI in at least one of their processes. But despite the operational efficiencies that AI and workflow automation promises …

Organizations are not realizing the returns and productivity gains they were targeting with AI.

What’s the disconnect?

There are a few ideas that come to mind:

Companies are chasing shiny objects and not being strategic about where AI should be applied in the business.

High computation costs to support the use cases in production.

Lack of skilled talent that understands how to extract the full potential from AI.

Insufficient training on AI solutions that are rolled out.

AI seems to be benefiting individual contributors, and not the organization as a whole … yet.

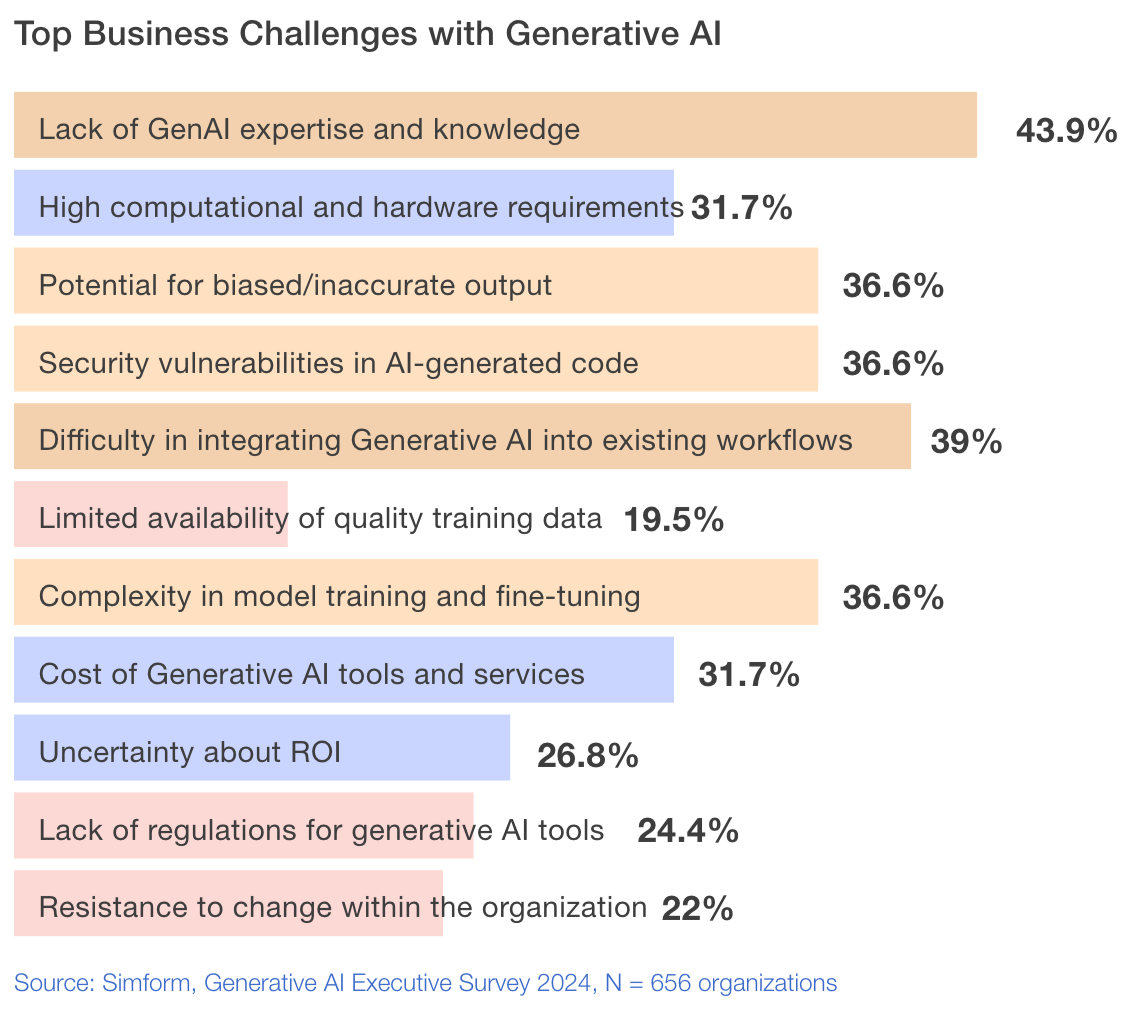

In 2024, Simform conducted research with over 600 global executives about their experiences with Generative AI to get further clarity about adoption and challenges organizations are encountering that cross borders.

Here is what they found:

Turns out - AI is not an easy drop in the bucket, as most would have hoped.

The way AI adoption is playing out is not new.

We know that history tends to repeat itself, and we, as humans, are more predictable than we think.

In fact …

In 1987, Robert Solow saw a similar trend and lack of promised productivity gains with the rise of computational power that became broadly available to organizations.

This Solow’s famous saying nicely summarizes the sentiment at the time “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

This trend was termed “The Solow Paradox.”

In the 1980s, there was a significant surge in the development and adoption of computers and information technology across various industries.

Personal computers were becoming more common in workplaces, and businesses were investing heavily in IT infrastructure to support the needs to operate those machines.

In addition, the U.S. economy was recovering from the economic stagnation of the 1970s and early 1980s, which included periods of high inflation and unemployment. Policymakers and economists were laser focused on improving productivity and economic growth.

But the aggregate productivity statistics did not show the expected increase. Productivity growth rates were relatively flat or growing at a slower pace than anticipated, leading to a disconnect between technology investments and economic output.

So why were the companies not repeating the benefits of the new technology?

The computers and information technology of the 1980s and 1990s were indeed powerful and capable of transforming business processes, increasing efficiency, and boosting productivity. It was clear that the new technology had the capacity to deliver substantial improvements.

The key problem was with the way organizations rolled out the technology.

Several factors contributed to the poor realization of productivity gains:

Lack of Complementary Changes: Simply installing new technology without making necessary changes to organizational structures, processes, and workforce skills limited its effectiveness. Businesses often failed to redesign workflows or train employees adequately to use the new technology.

Adaptation Period: There was a lag between the adoption of technology and the realization of its benefits. Companies needed time to learn how to best utilize the new tools, which delayed observable productivity gains.

Management Practices: Inefficient management practices and resistance to change also hindered the effective deployment of IT. Managers might not have fully understood how to leverage technology for strategic advantage.

Measurement Challenges: Traditional productivity metrics might not have captured the gains accurately, especially in service industries where outputs are harder to quantify. The benefits of IT in areas like improved customer service or decision-making efficiency might not have been reflected in conventional productivity statistics.

Bottom line:

To fully capitalize on the potential of IT, organizations needed to invest in complementary assets, such as new business processes, organizational restructuring, and human capital development. Without these, the technology’s capacity couldn’t be fully exploited.

AI requires you to understand...

That implementing AI isn't as simple as flipping a switch. The hype might be cooling, but the real work is just beginning.

Here's the deal:

Get strategic. Stop chasing shiny AI objects. Figure out where AI can truly move the needle for your business.

Brace for impact. AI will shake things up. Be ready to overhaul processes, reskill your workforce, and maybe even restructure your org chart.

Play the long game. Remember Solow's Paradox? Productivity gains from new tech don't happen overnight. Patience is key.

Learn from history. We've been here before with computers in the '80s. Let's not repeat the same mistakes.

Are we ready to learn from the past and build a smarter AI-powered future?

That's the million-dollar question.